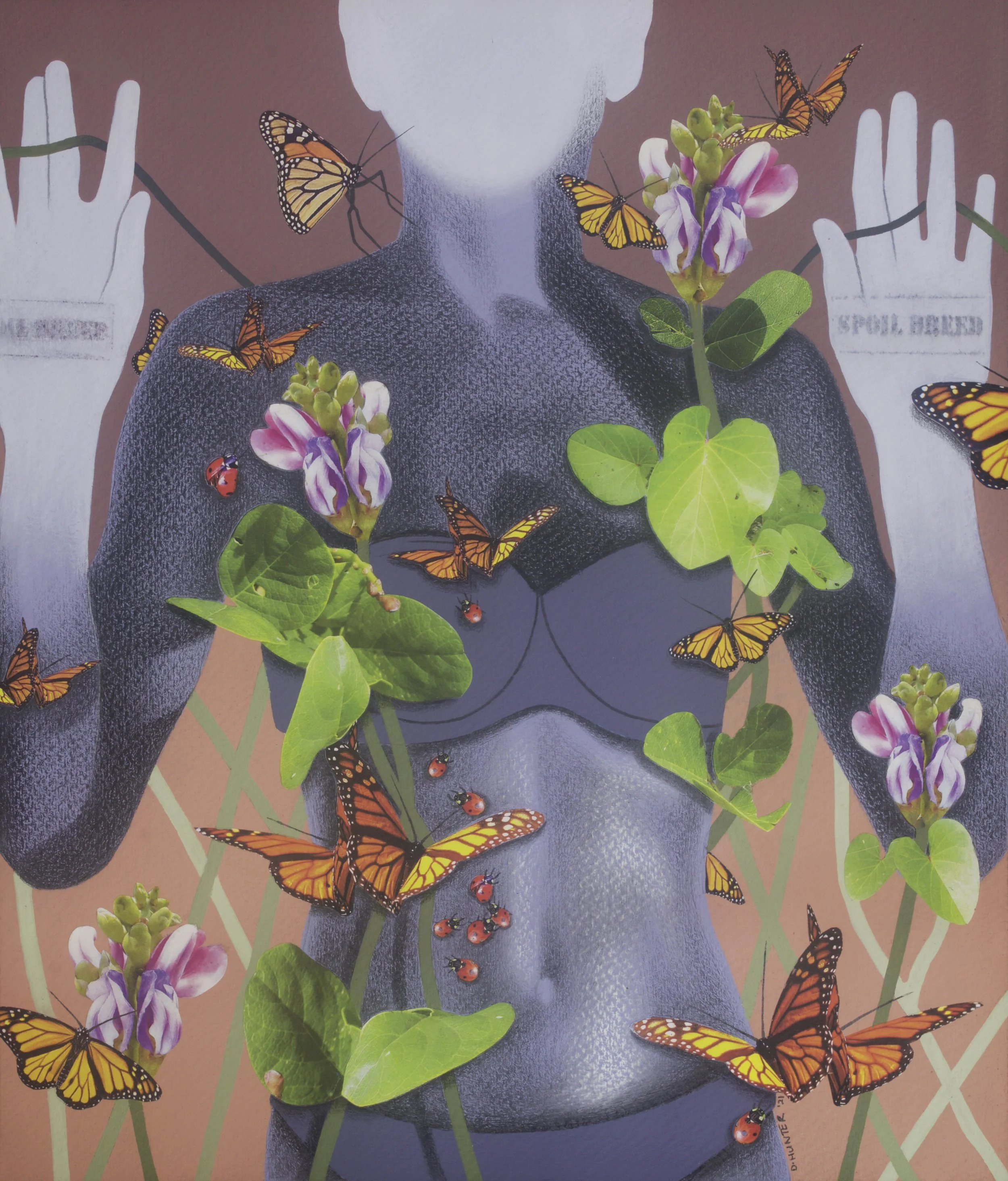

A Floriography for Dominique Hunter (or, Morning Glory Strategies for those who choose to remain)

This piece was published as part of Burnaway’s 2024 editorial theme “CRUSH”.

“So, we persist. We do not give much thought to this back and forth, this act of going and coming, uprooting and transplanting. It is simply what we do. It is what we have always done, all of us, in some way. That is our history and it is our future. Ours is a collection of personal truths forever intertwined with the perplexing tendrils of shifting roots.”

Dominique Hunter, “Transplantation”

Faceless gray and white figures writhing, rolling, or relaxed in contrapposto. The liminal beings and suspended scenes in the work of Dominique Hunter act as avatars, a self-portrait, and an Eden for the yearning, heaving imaginary. She inserts fragmented parts of herself into the mixed media works: a slender feminine figure, portions of melanated skin, the visible signs of a maker slumped or draped over a desk. Hunter’s displaced depictions of self speak to the demographic of Caribbean creatives committed to living in motherlands that can feel like “otherlands,” specifically spaces of colonially rooted othering. As an artist living and working in Guyana, Hunter must contend with the social pressures and barriers to access that can often come with choosing to build a practice locally, within the region. This is no small task when the dominant paradigm in your local space assumes that as an artist one must move into the diaspora to find professional and creative success. Further, Hunter has had to endure the skepticism at choosing to return home after studying abroad—an experience we both share and have admittedly commiserated over as creative practitioners trying to make art and culture work sustainable in our home spaces. Her work is for those who bear the weight of remaining.

To give some context, a third of Guyana’s population lives in the diaspora. For Guyanese creatives, there is a particular colonial vibration to the palpable public desire to leave, to go elsewhere. As curator and academic Grace Aneiza Ali aptly put it, “migration swirls around Guyanese people.” For those living in the region with privilege or means, migration and movement are simply a fact of life: for medical care, education, stocking up on supplies deemed too niche to be imported. As Hunter asserts above, for those who belong to a people largely comprised of those from elsewhere, mobility and nomadism are ingrained and familiar parts of the past, the present, and an increasingly precarious future. But what of the heaviness of those who remain? Those who feel they have sacrificed access and opportunity for the sake of loyalty to the landscape? What is the weight of a heart set on staying?